Due to the limitations on presenting and accessing the source material required for the discussion to continue here, I'll confine my wrap-up of the Brandenburg report to the excerpts already presented, under the presumption that they are still allowed.

As I mentioned previously, the entire report suffers the effects of inexpert translation—not just in its pidgin English but in its misapprehension of the technical details of the source material. These kinds of report are generally worded carefully in their native languages because they often will be considered evidence at law and may be tested as such. The present English translation misses the mark by a country mile. The bulk of the report is a technical description of the examinations performed and tables of resulting data, thus fairly unremarkable and nonprobative. However the operative language is in the apparently conclusory statements, some of which have been preserved in our record here. I was able to discuss them with my colleague, a native German-speaking engineer prior to the weekend. In some cases he was able to offer speculative reconstructions of the likely German text and offer other options for translation and expert interpretation.

Returning to the paragraph I excepted, I challenged our claimant to interpret these sentences.

A destruction of the lamellae has occurred which cannot occur by any comparable mechanical technological influence. The processes of explosive treatments of metallic materials as for example explosive hardening and explosive cladding have to be excluded. These processes show in surface-near areas comparable effects.

The phrase, "mechanical technological influence," is almost certainly a strained translation of a specialized German engineering idiom that we would best translate as "manufacturing process." It does not mean simply all conceivable mechanical effects. The mention of explosives here seems like a dog whistle, and the repetition of "comparable" (which may have come from any of several German words) seems to paint the conclusion that the author is here saying the observations are attributable to explosive effects apart from any other possibility. Instead the author is more likely saying that because they know where the specimen came from, they know how it was manufactured and can rule out any manufacturing process (including but not limited to explosive forming) as the cause for what they have observed. The author is

not at all saying that the effects cannot be attributed to any purely mechanical process and must therefore be attributed by default to an explosion.

It's not really a nit-pick to say that "surface-near" is a poor translation of

oberflächennah. It's unfortunate that English has no single word to succinctly translate to, but making up one is not how conscientious translation proceeds. Words matter, especially when translating something that was specifically worded to begin with.

The next excerpt is one we discussed already in our previous treatment of the Brandenburg report.

These plastic deformations in the micro range do indicate exposure to extremely heavy shock forces such as happens from the effects of a substance detonating.

In the previous discussion it was argued that this language means to dispositively attribute a cause.

It expressly does not. It did not then, and it has not suddenly acquired that meaning in the interim. This language—whether in English or German—says merely that an explosion

can have caused those effects. It specifically avoids saying it

must have caused them. This is a very important distinction that may not simply be brushed aside.

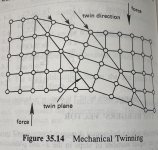

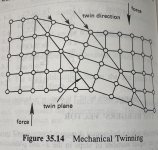

The "plastic deformations" mentioned here are the infamous twinning, which we have discussed at length at least twice previously. Here is the diagram from the engineering license exam study guide.

The statement in the report conveys the wrong impression that twinning is caused exclusively by shock forces that can only be produced by an explosion—or at least that's how some here have tried to interpret it.

That is absolutely untrue.

In fact, when twinning is introduced in metallurgy classes, causes such as explosives aren't even mentioned. High strain rates can cause it. But there are countless ways for high enough strain rates to occur. Ordinary forces applied at extremely low temperatures can cause twinning, but also larger forces at only relatively low temperature—forces consistent with the violent breakup of a ship. That's where our previous discussion of a running shear comes in. Cyclical loading can cause twinning, and we know the specimens came from a part of the ship highly likely to be subject to cyclical loading from waves and from the operation of the bow visor and car ramp. Ordinary fatigue forces can cause twinning, and also the highly localized hardening the laboratory observed.

The Brandenburg authors are not being dishonest for failing to mention these causes. Nor has the translator committed any grave sin in this passage. Their statement is true, but not the whole truth. It is neither dispositive and exclusive. We'll come back to this.

Our final excerpt happens to be the final statement in the summary portion of the report.

It has to be concluded that the pressure waves also in areas, where by means of light microscopes, only little deformation is recognizable, did result in hardening due to structure deformation in the micro range; (deformation of the perlite grain, change of the solidification density).

The highest hardening has been established in way of the immediate fracture area of the specimen being most strongly strained.

For this hardness increase as well as for the determined structure deformations detonative influence is probable.

My colleague offers three or four German words that can all have been translated as "probable." Two of them also embody lesser degrees of certainty, such that we would more accurately translate them as "plausible" or "credible." As you can imagine, the choice of English word here determines much of the question. And our translator has not earned a reputation for accurate word choices. To adopt the common English meaning of "probable" to indicate a likelihood, a comparative analysis must support it. No such comparative analysis appears in the Brandenburg report. The SwRI report indicates that they would be willing to conduct such an investigation for an additional fee. But because the Brandenburg report does not lay out a comparative analysis, "probable" is the wrong word. In keeping with the conservative nature of these reports, "plausible" or "credible" is the better translation.

Now we circle back to the loaded question. I noted that the SwRI report was worded carefully to support the notion that an explosion

could have caused the effects they saw, but that it was by no means the only or best explanation. Brian Braidwood took it upon himself to interpret these reports, and we don't have to search very hard in his analysis to find his statements that indeed the labs were not told to perform a comparative analysis of potential causes, but were simply asked to determine whether the damage to the metal

could have been caused by an explosion irrespective of any other cause. That is by no means an inappropriate question to ask a metallurgy lab to answer, since a fully comparative analysis is often beyond their scope. But to frame the findings as discriminatory of cause and a dispositive attribution is quite irresponsible. The comparative analysis must be done if a differential diagnosis is to ensue. The labs didn't do it, and Braidwood simply restated the findings of the laboratories misleadingly as dispositive. This is the kind of shuffle we see all the time among proponents of fringe theories.

Properly translated and properly contextualized into the laboratory's remit, the Brandenburg report does not provide evidence that preferentially establishes an explosive detonation as the cause for the damage to the steel specimens.