Music notation must be, along with that of sub atomic particles, be the most unfriendly thing for noobs to fathom.

Either you are some musical specialist, or it is just some kind of secret code, you can't understand. There is no in between.

In other words.

Pretending (well there's no pretending, as it is actually true) that my knowledge of music is what I've learned at highschool and that there are 7 notes; do re mi fa sol la si (and then it starts again, but a bit higher in tone), and that I know that you can play notes of longer and shorter duration.

Could you explain in English please?

Well, the linked video goes into pretty good detail in plain English. I really don't know that I could do a better job of it. But here goes:

Do-Re-Mi is what is called a

diatonic scale. You have seven notes before the first one repeats in a higher register. The top and the bottom are both called Do because the higher one is double the frequency of the lower one. They sound like the same note - if you play the two together there is no harmony, there is just one note. It's called an

octave because there are eight notes in a diatonic scale.

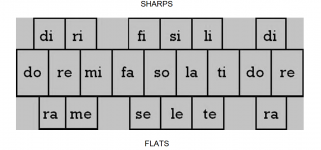

However, there are notes between the Do-Re-Mi. There's a note halfway between Do and Re. Do-and-a-half if you like. For this reason we will be swapping to the traditional letters to refer to the notes. Don't ask why it starts at C. (quick answer: it doesn't always)

Do = C (a deer, a female deer)

Re = D (a drop of golden sun)

Mi = E (a name I call myself)

Fa = F (a long long way to run)

So = G (a needle pulling thread)

La = A (a note to follow So (cop out!))

Ti = B (a drink with jam and bread)

Do = C' (an octave higher)

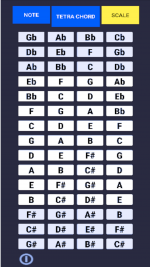

The note halfway between C and D is either C sharp or D flat. Sharp means a half-step up, and we use the hash symbol for it: #. So C# is C-sharp and is halfway between C and D. Flat means a half-step down, and we use a special symbol that is approximated in text by a lower case b. So Db is half way between D and C. So in fact there are more than 8 notes. For reasons that are complicated, E# = F and Fb = E. Similarly, B# = C and Cb = B. You'll need to accept that without explanation - it just is. So this means that there are in fact 12 notes in the scale.

Now, in Equal Temperament, which was only widely adopted in the 18th century, the frequency of C# is exactly halfway between C and D. So C# = Db always. In previous systems of tuning, this was not the case.

Remember how I said you shouldn't ask why it starts at C? Okay, now you can ask. Starting at C means you are in the

key of C, but you can be in other keys. This means that while the intervals (distances) between notes are the same, you start at a different note. So this is Do-Re-Mi in D. Notice that you can only get the same intervals by using sharps. In the key of D it is traditional to use sharps and not flats.

Do = D

Re = E

Mi = F#

Fa = G

So = A

La = B

Ti = C#

Do = D'

Being in the

key of D means that most (but not all) of the notes you will be playing come from this scale. If I were going to be precise, this is the key of D major, but that's not important right now. Know that there is also a D minor, in which the intervals between the notes are not the same.

Prior to Equal Temperament, an instrument was tuned so that

this particular key was most harmonious, at the expense of other keys not being harmonious at all. If you wanted to play in a different key, you had to retune your instrument. Not particularly difficult for wind instruments, tedious and time consuming for stringed instruments, and all but impossible for keyboard instruments. Under these systems (and there were a variety of them) C# was not the same as Db.

J.S. Bach's 1722 collection

The Well-Tempered Clavier was in essence a demonstration of how under Equal Temperament, a single instrument could play in all keys. It consists of a prelude and a fugue (those are musical structures or forms) in each of the major and minor keys, so 24 preludes-and-fugues all together. And then there are two books so in fact it's 48. It's beautiful - I recommend it.