The Great Zaganza

Maledictorian

- Joined

- Aug 14, 2016

- Messages

- 29,736

there is a very strong correlation between living for more than a hundred years and having a birthplace with shoddy recordkeeping of birth certificates.

Heh, beavers, heh heh

And/or generous pension provisionthere is a very strong correlation between living for more than a hundred years and having a birthplace with shoddy recordkeeping of birth certificates.

Dammed predictive text!

World’s Largest Beaver Dam

parks.canada.ca

A beaver damn that's 800 meters long.

2025 is … was the international year of quantum science and technology. Yes because quantum tech is increasingly important, but especially because quantum mechanics was invented 100 years ago this year. In 1925, our strangest true theory went from being a peculiar set of ideas to describe some funny results from experiments, to a full-blown theoretical framework that overturned how we think reality really works. So today, as the centenary year approaches its end I want to take you on a little journey through what may be the most paradigm-destroying several months in scientific history.

I haven't watched the video yet, but I was fascinated when I started learning to play an instrument at about 40 years old. I wanted to know why things were the way they are and learned a lot about music theory. I eventually made my own transposing wheels (which I later found out are available in several different forms, in abundance.)

I can certainly tell where a certain Error sound came from...I was a little bit suspicious at first about the heavy use of AI-generated imagery, but the content of the video was sound.

Yes, I used a pun. Deal with it.

I think it does cover that. Not "cannot", but "do not". He explains that using more notes would make notation much more difficult but yes, it's not going to change now.Actually the video does not fully answer the question. We could equally have 16 notes in an octive. The main reason we

cannot is that so much music has been written with the 12 notes.

Music notation must be, along with that of sub atomic particles, be the most unfriendly thing for noobs to fathom.Under equal temperament, D# is the same as Eb, but under other temperaments, it isn't.

0-3-5?I'm a guitarist I don't need to know musical notation.

It's against the rules.

I’m a bass guitarist, so completely disregard it anyway.I'm a guitarist I don't need to know musical notation.

It's against the rules.

Well, the linked video goes into pretty good detail in plain English. I really don't know that I could do a better job of it. But here goes:Music notation must be, along with that of sub atomic particles, be the most unfriendly thing for noobs to fathom.

Either you are some musical specialist, or it is just some kind of secret code, you can't understand. There is no in between.

In other words.

Pretending (well there's no pretending, as it is actually true) that my knowledge of music is what I've learned at highschool and that there are 7 notes; do re mi fa sol la si (and then it starts again, but a bit higher in tone), and that I know that you can play notes of longer and shorter duration.

Could you explain in English please?

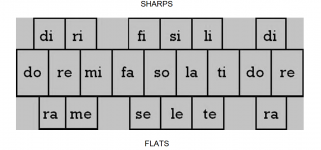

All that took me years to learn, but then I never had it explained so concisely. Everybody knows Do-Re-Mi, but far fewer know the interstitial Solfege names. Here's a full chart (The standard major scale is in the middle line, sharps above, and flats below their related notes):Well, the linked video goes into pretty good detail in plain English. I really don't know that I could do a better job of it. But here goes:

Do-Re-Mi is what is called a diatonic scale. You have seven notes before the first one repeats in a higher register. The top and the bottom are both called Do because the higher one is double the frequency of the lower one. They sound like the same note - if you play the two together there is no harmony, there is just one note. It's called an octave because there are eight notes in a diatonic scale.

<snipped>