Rolfe

Adult human female

I have found it difficult to find a single article that goes through the explanation properly, which is still non-technical enough to be readable. I've read quite a number of articles to put it all together.

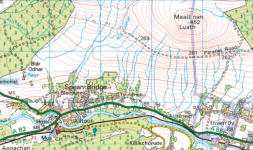

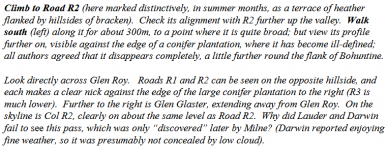

The article that Pixel linked to gives a good account of Darwin's mistake. He was a relatively young man, just home from the voyage on the Beagle, and in the process of formulating his thoughts on the origin of species. He had become enamoured of a theory of "tectonic uplift", which posited that the continents were rising and falling with respect to sea level, in equilibrium and in balance. This theory, for reasons I don't quite understand, was at that time important to his theory of the origin of species, and he was looking for confirmatory evidence. He heard about Glen Roy, and thought this was the evidence he needed. He developed a hypothesis whereby Glen Roy (and the adjacent Glen Gloy and Glean Spean) had at one time been below sea level, and the "roads" were evidence of three shorelines that had formed at different times as the land rose out of the ocean. He put this together in a paper which he presented to the Royal Society, and it was this piece of work (which was complete nonsense) that got him his membership of the society.

Ironically, by the time he came on the scene in 1838, the real explanation had already been worked out by a couple of people, with a rich amateur naturalist by the name of Lauder getting very close to the answer. Earlier in the 19th century the idea that these were sea shores had already been considered and tossed out, for a number of very good reasons.

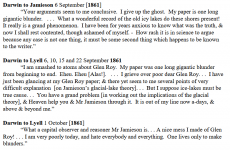

Some years later, when his evolving theory of the origin of species no longer relied on the tectonic uplift theory, and when the most puzzling aspect of the loch-shore theory was finally elucidated beyond any doubt, he gave in, describing his adherence to the seashore theory as his "greatest blunder".

The article that Pixel linked to gives a good account of Darwin's mistake. He was a relatively young man, just home from the voyage on the Beagle, and in the process of formulating his thoughts on the origin of species. He had become enamoured of a theory of "tectonic uplift", which posited that the continents were rising and falling with respect to sea level, in equilibrium and in balance. This theory, for reasons I don't quite understand, was at that time important to his theory of the origin of species, and he was looking for confirmatory evidence. He heard about Glen Roy, and thought this was the evidence he needed. He developed a hypothesis whereby Glen Roy (and the adjacent Glen Gloy and Glean Spean) had at one time been below sea level, and the "roads" were evidence of three shorelines that had formed at different times as the land rose out of the ocean. He put this together in a paper which he presented to the Royal Society, and it was this piece of work (which was complete nonsense) that got him his membership of the society.

Ironically, by the time he came on the scene in 1838, the real explanation had already been worked out by a couple of people, with a rich amateur naturalist by the name of Lauder getting very close to the answer. Earlier in the 19th century the idea that these were sea shores had already been considered and tossed out, for a number of very good reasons.

- there were no sea shells anywhere in the glen, not on the "roads" or on the bottom

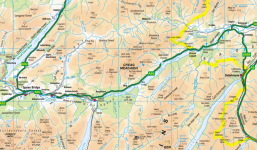

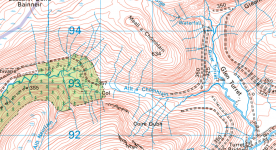

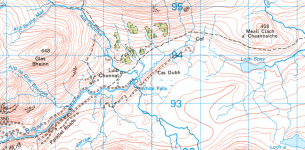

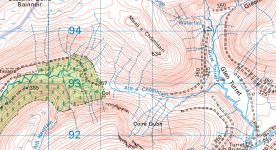

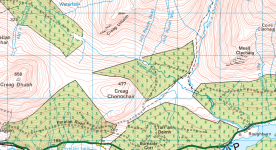

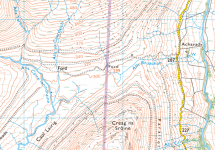

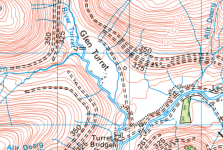

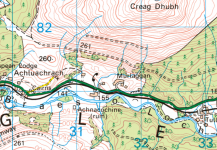

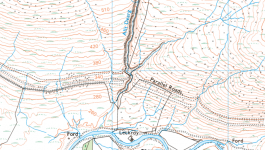

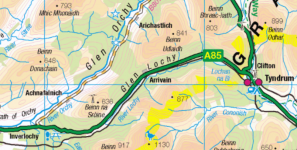

- the "roads" are confined to Glen Roy, Glen Gloy and Glen Spean, without a dicky-bird to be found in, say, Glen Loy or the slopes overlooking Loch Eil or Loch Arkaig, never mind anywhere else in the country

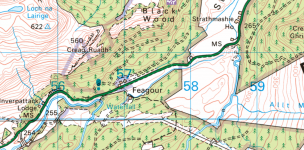

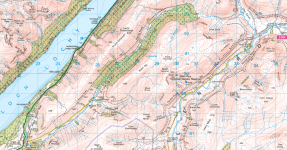

- the lines perfectly follow the contour lines, suggesting almost supernatural preservation of the contours of the landscape even as it rose a thousand feet out of the ocean

- the roads are vertically narrow, inconsistent with tidal shorelines, or even ocean breakers

- there was no explanation for the very precise heights of 355, 350, 325 and 260 metres forming these shorelines in different places as the land rose (why no 325 or 260 lines in Glen Gloy, why no 325 or 350 lines in Glen Spean?)

Some years later, when his evolving theory of the origin of species no longer relied on the tectonic uplift theory, and when the most puzzling aspect of the loch-shore theory was finally elucidated beyond any doubt, he gave in, describing his adherence to the seashore theory as his "greatest blunder".