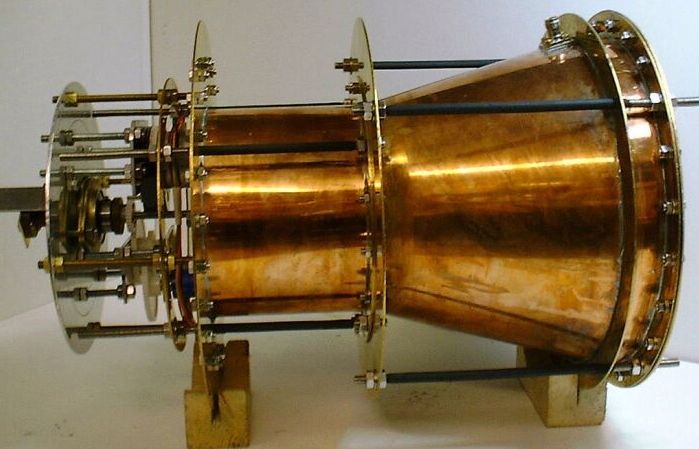

Shawyer’s paper basically describes particles bouncing elastically off walls; that is the way that he derives the force that gives the ‘thrust’ for his ‘drive’. But the stuff he injects into his truncated conical device is microwaves. Most people would ask: how does that work?

Microwaves, like everything in the Universe, can be described in terms of ‘waves’, or in terms of ‘particles’. If asked to explain how they reheated my spaghetti bolognese this evening, I would use the ‘wave’ description as the easiest one. But Shawyer is absolutely justified in switching between a ‘wave’ description and a ‘particle’ description, whenever he felt like it (in fact, practically every other sentence of his paper). The only problem is that, unless you intimately know the equations that he throws around like confetti at a wedding, his unclear and badly explained twists and turns are likely to leave you wondering whether he really must be a genius of Einsteinian proportions. (This is an unfortunate misconception that many people have: that a genius is someone who says things that no one else can understand. The truth is that a genius is someone who can make every-one understand.)

The net result is the following. Forget all of the stuff in Shawyer’s paper that talks about ‘group velocities’ and ‘wavelengths’ and ‘Q factors’. Just concentrate on his diagrams of little photons (microwave particles) bouncing around inside his contraption, and the physics equations he writes down to go with those bouncing particles. Take it from me that he’s right about that, and strip out all the really scary looking equations that have Greek letters in them.

Now remember your high school physics, and look at what’s left.

Start with Shawyer’s Figure 2.4. He shows his truncated conical contraption, with a particle bouncing around inside it. It must have a constant energy, because it’s being reflected elastically at every wall. That means that the magnitude of its momentum, p, is constant.

As Shawyer correctly shows, the particle reflects off each wall in the way that you learnt at school (angle of incidence equals angle of reflection). But because the walls are inclined to the ‘axial’ direction (the axis going down the middle of the cone), this means that the angle that their momentum

makes with the axial direction becomes ‘steeper’ at the narrow end of the cone, and ‘shallower’ at the bigger end of the cone. If you draw a few diagrams, and use some high school geometry, you can work out how much ‘steeper’ and ‘shallower’ the particle’s momentum angle gets, each time it bounces off a wall. Shawyer’s Figure 2.4 correctly shows this phenomenon.

Now look at the arrows below the diagram in Shawyer’s Figure 2.4. If you remember your high school physics, these are force vector arrows. They show the direction and strength of the force that the particle imparts on each wall as it hits it.

Shawyer’s F1 is the force on the ‘large’ end of the cone, and F2 is the force on the ‘small’ end of the cone. As he correctly shows, F1 is bigger than F2, because the particle’s momentum is much closer to ‘head on’ to the large end. (Remember, the size of the particle’s momentum does not change, only the direction it is heading in.)

After going through a few more trips into wave-land, Shawyer computes the difference between F1 and F2. That’s where his ‘drive’ comes from. All the complicated equations he throws in are just fluff around this basic result.

What’s wrong in Shawyer’s paper

Now we get to the point that a number of people have already made, but perhaps not confidently enough. Look at the arrows that Shawyer labels ‘Fs1’ and ‘Fs2’ on his Figure 2.4. These are supposed to be the forces that the particle imparts to the wall of the conical part of his contraption.

But hang on a minute! When a particle bounces elastically off a wall, doesn’t the wall feel a force that is perpendicular to the wall? Of course it does: if you remember your high school physics, you subtract the initial momentum vector from the final momentum vector, and the resultant force points into the wall. (OK, it’s actually called the ‘impulse’, not the force, but it’s effectively the same thing for what we’re talking about here).

Now look back at Shawyer’s Figure 2.4. He has Fs1 and Fs2 pointing perpendicular to the axial direction, not perpendicular to the cone’s walls.

His arrows are wrong.

This is the fundamental blunder that renders Shawyer’s paper meaningless. If you remember your high school physics, it is simple enough to draw a diagram to prove to yourself that, when a particle bounces off the wall of the cone, the increase in the particle’s momentum in the axial direction is exactly balanced by the impulse imparted to the cone in the opposite direction.

This is what has already been argued by those who have bothered to wade through Shawyer’s paper. It is not affected by all the ‘wave-land’ equations that Shawyer throws in. It is the fundamental error in his analysis.

So what do we really find out from this analysis, when we do it correctly? Simply this: when a particle bounces around elastically inside a closed container, neither of them go anywhere. If you start in the right reference frame, then when the particle is moving left, the container is moving right; when the particle is moving up, the container is moving down; and so on. When the particle and the container collide, the directions of motion change, but their momenta still add up to zero. Nothing accelerates.

There is no ‘drive’.

How does Einstein’s theory of relativity change things?

That heading should be enough to have scared most people off reading this sentence. Relativity is really complicated, right? Must be—Einstein invented it.

Shawyer throws relativity into his paper, if only because he really can’t avoid it for a particle that moves at the speed of light (well, is light, or its cousin, anyway). Maybe some weird spooky relativistic effect makes Shawyer’s scam drive work?

Fortunately (for us, not Shawyer), relativity doesn’t change a thing. I purposefully described everything above in terms of momentum. It turns out that one thing that relativity does not change is that momenta can still be added together, just like they can in Newtonian mechanics.

So the answer to the question in the previous heading is: Not at all.

Shawyer’s ‘electromagnetic relativity drive’ is a fraud.

Good one!

Good one!