a_unique_person

Director of Hatcheries and Conditioning

There's some really good YouTube videos out there that explain it all in terms even I can understand.

The saxophone family shows this the best. The basic saxophone that everyone knows - the one that goes up after the bit you blow in then down, which is the bit you hold, then up again for the end - is the tenor saxophone and it is tuned to Bb. In other words, a Bb played on a tenor sax is a concert C. The next smaller saxophone is the alto sax, which is in Eb. And it switches between them going up and down the sizes - the soprano sax above the alto is in Bb, the baritone sax below the tenor is in Eb. Technically there are nine different sizes of saxophone, but really only these four are in general use.But then, I encounter trumpet players in my own band that have been playing 50 years or more that don't know that their Concert B-flat is actually a C for their instrument's notation. I.E., when he plays a C, the note is actually a B-flat when played on a piano or other "concert" instrument.

I even made an app where you can choose to play notes, chords (tetrachords), and scales. I'm really proud of it but had basically zero downloads. It's no longer available.

That's not actually all that unusual. I never played clarinet, but oboe and flute also have different fingerings for the higher registers. It's something something because you have to overblow to get a higher harmonic wave.The clarinet is particularly strange. It can do three octaves, which makes it versatile, but in the highest range the notes have different fingerings to the other two octaves.

Thank you for this explanation.Well, the linked video goes into pretty good detail in plain English. I really don't know that I could do a better job of it. But here goes:

Do-Re-Mi is what is called a diatonic scale. You have seven notes before the first one repeats in a higher register. The top and the bottom are both called Do because the higher one is double the frequency of the lower one. They sound like the same note - if you play the two together there is no harmony, there is just one note. It's called an octave because there are eight notes in a diatonic scale.

However, there are notes between the Do-Re-Mi. There's a note halfway between Do and Re. Do-and-a-half if you like. For this reason we will be swapping to the traditional letters to refer to the notes. Don't ask why it starts at C. (quick answer: it doesn't always)

Do = C (a deer, a female deer)

Re = D (a drop of golden sun)

Mi = E (a name I call myself)

Fa = F (a long long way to run)

So = G (a needle pulling thread)

La = A (a note to follow So (cop out!))

Ti = B (a drink with jam and bread)

Do = C' (an octave higher)

The note halfway between C and D is either C sharp or D flat. Sharp means a half-step up, and we use the hash symbol for it: #. So C# is C-sharp and is halfway between C and D. Flat means a half-step down, and we use a special symbol that is approximated in text by a lower case b. So Db is half way between D and C. So in fact there are more than 8 notes. For reasons that are complicated, E# = F and Fb = E. Similarly, B# = C and Cb = B. You'll need to accept that without explanation - it just is. So this means that there are in fact 12 notes in the scale.

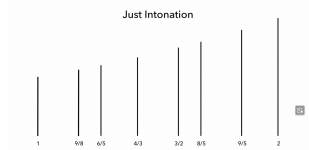

Now, in Equal Temperament, which was only widely adopted in the 18th century, the frequency of C# is exactly halfway between C and D. So C# = Db always. In previous systems of tuning, this was not the case.

Remember how I said you shouldn't ask why it starts at C? Okay, now you can ask. Starting at C means you are in the key of C, but you can be in other keys. This means that while the intervals (distances) between notes are the same, you start at a different note. So this is Do-Re-Mi in D. Notice that you can only get the same intervals by using sharps. In the key of D it is traditional to use sharps and not flats.

Do = D

Re = E

Mi = F#

Fa = G

So = A

La = B

Ti = C#

Do = D'

Being in the key of D means that most (but not all) of the notes you will be playing come from this scale. If I were going to be precise, this is the key of D major, but that's not important right now. Know that there is also a D minor, in which the intervals between the notes are not the same.

Prior to Equal Temperament, an instrument was tuned so that this particular key was most harmonious, at the expense of other keys not being harmonious at all. If you wanted to play in a different key, you had to retune your instrument. Not particularly difficult for wind instruments, tedious and time consuming for stringed instruments, and all but impossible for keyboard instruments. Under these systems (and there were a variety of them) C# was not the same as Db.

J.S. Bach's 1722 collection The Well-Tempered Clavier was in essence a demonstration of how under Equal Temperament, a single instrument could play in all keys. It consists of a prelude and a fugue (those are musical structures or forms) in each of the major and minor keys, so 24 preludes-and-fugues all together. And then there are two books so in fact it's 48. It's beautiful - I recommend it.

The tenor sax is my instrument of over 25 years. Part of my initial curiosity was why the alto music was in a different key.The saxophone family shows this the best. The basic saxophone that everyone knows - the one that goes up after the bit you blow in then down, which is the bit you hold, then up again for the end - is the tenor saxophone and it is tuned to Bb. In other words, a Bb played on a tenor sax is a concert C. The next smaller saxophone is the alto sax, which is in Eb. And it switches between them going up and down the sizes - the soprano sax above the alto is in Bb, the baritone sax below the tenor is in Eb. Technically there are nine different sizes of saxophone, but really only these four are in general use.

One of my music teachers had a C melody sax, which used to be popular but are quite rare now.

The tenor sax is similar. I never really even learned how to use the higher note keys because my band music never called for them. There are also alternate fingerings for a few notes. It's a complicated instrument, with all those keys and rods!The clarinet is particularly strange. It can do three octaves, which makes it versatile, but in the highest range the notes have different fingerings to the other two octaves.

The clarinet is particularly strange. It can do three octaves, which makes it versatile, but in the highest range the notes have different fingerings to the other two octaves.

Thank you for this explanation.

I've tried to follow the Youtube, but he lost me at the overtones.

Well, not the concept of the overtones, but then what he called them. (at about 4:50 in the video)

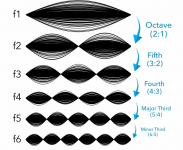

From f1 to f2 it is an octave. I can see that, there are 2 waves and thus the tone should be an octave higher. I get that.

But then he calls the f4 overtone a fourth, where this should also be called an octave, as here we have 4 waves on the string, and thus the tone should be twice as high as the F2 and 4 times as high as the f1.

But suddenly it is not an octave anymore? It is things like this that make music so difficult to follow. There are definitions, but after a while these are simply changed into something else, without explaining why this is.

...

And then he puts them in a complete different order as what is explained above.

Major confusion in my head here.

Or Armageddon with anyone who knows anything about science.Or F1 with a bunch of racing fans, or Armageddon with a bunch of oilfield workers, or Gran Turismo with a bunch of gamers/geeks/nerds

"If it sounds good, it is good." -- Duke EllingtonBecause that's not the sequence it follows.

Music is often lauded as being strictly mathematical but in fact it isn't. A lot of what makes up music is arbitrary and only done because it's "traditional".

"If it sounds good, it is good." -- Duke Ellington

There's a lot more than that. I also studied electronic music, and one of the subjects was how you could turn a sine wave into other kinds of wave by adding harmonics to it. Eg. if you add only odd-numbered harmonics, you approach a square wave (you'd have to add an infinite number of them to reach a square wave exactly). Basically every sound that comes out of an electronic synthesiser is a sine wave with added harmonics.There is a science to it if you analyse the harmonics of a single single note played on an instrument they will include the 5th and the 3rd, for example.