Have you considered writing in a memory safe language such as Logo or Python?

Yes. We use Python extensively for in-house software. And some of our newer supercomputing applications are written in Python using its modules for parallel computation. I'll try to explain the paradox without derailing too much from software quality in general into specialized software techniques for supercomputing.

Memory-safe is a synonym for memory-managed. In a memory-managed language, the final code uses a language-specific runtime to manage the assignment of RAM to program structures and its subsequent recovery to avoid memory leaks. This comes at a computational and storage overhead. For computation, every reference to a program variable must be wrapped in additional code to interface with the memory manager and assure the correct dereference. For storage, the runtime must maintain its own metadata to organize the program storage which may exceed the actual program storage by a significant margin (or even a factor). This is often too much overhead and we have to turn to specialized Python modules to try to get around it.

The paradox is that both very small computers and very large computers achieve their desired ends by staying as close as possible to the bare metal. Our embedded data concentrators don't do

any memory allocations on the fly, for example, and use CPU-specific SIMD instructions to eke the most performance out of the least silicon (i.e., the most robust silicon for hostile environments). Similarly our cluster-oriented software often uses hand-optimized code to avoid even normal overhead of general computing—cache behavior, for example. That's because your largest computers are always being asked to solve the largest problems, where even a slight overhead multiplies across many days of computation and many pages of RAM. Being able to optimize frequently-used code segments at the hardware level can win you days. And being able to use RAM without memory-management overhead can mean the difference between 10 and 20 days of computation. Doing that in Python means essentially suppressing all the advantages you would ordinarily get from Python.

There are other considerations too. Supercomputing on clusters is not just running the same software as before, only on a faster computer. The program architecture has to take advantage of the knowledge that it's running on a cluster. And the parallelism relies on predictable per-node computation times. That sort of synchronicity is hard to achieve with language runtimes jittering up the program steps.

Ironically medium-sized computers solving medium-sized problems is where you see the advantage from easier-to-use, write-once-run-everywhere languages like Python. If a computation is going to take a "day," it's often unimportant whether that day is 12 hours of computations or 15 hours. In all cases you're going to start it in the morning and come back the next morning to get your answer. But for large-scale computers, your problem sizes are once again bumping up against the limits of the hardware and you want to start throwing out things you don't need in order to accommodate just the problem.

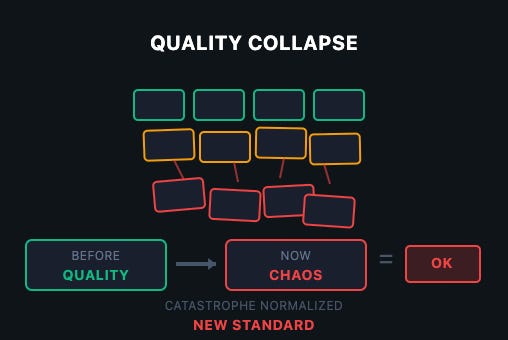

Really it comes down to development cost, which is where we circle back to the thread topic. A lot of consumer-facing software today is of poor quality because its owners are trying to minimize development cost. Every bank, for example, has an online banking application. The cost of developing and maintaining that code is overhead for the bank. So they're all looking for the ideal price point, and the consumer's tolerance for bugs, inefficient computation, or inexpertly designed interactions is a factor in that calculus. In cases like Apple's calculator app, the most cost-effective solution overall might simply be to expand the memory size of the typical MacBook and charge the customer $50 extra for it. And our medium-sized supercomputers solving medium-sized problems can often overcome limits simply by adding $10,000 worth of additional RAM to them, and that's cheaper than asking a senior software engineer to spend a week optimizing the code.

It's quite possible to achieve good memory behavior using the classic compiled languages. It costs more to develop, but that additional cost pays for itself over time in terms of other advantages in our specific use cases. If it takes you 112 megabytes on a personal computer to find the square root of 42, that's okay. If it's a problem, add RAM to the computer. But if you're simulating a nuclear exposition at centimeter resolution or solving a matrix in 10

12 unknowns, every CPU cycle and every byte of memory still counts, and the best solution isn't always an incremental augmentation. Solving those gargantuan problems in finite time on the best hardware you can muster still means keeping your eye on the sparrow, ignoring the fact that there are trillions of sparrows.

The other problem is that a lot of the hard code is already written and debugged in the classical languages. This is often

extremely difficult code derived from math that would make your eyes bleed. Its correct implementation on a computer is therefore often prohibitively difficult to verify. Once you've done it, you're reluctant to do it again. Hence rewriting it all from Fortran to Python is not a light undertaking. Thankfully Python provides a robust method (libpython) for Python programs to access compiled code in other languages. But then again in order to use it you typically have to sidestep Python's memory manager.